It occurs to me that it takes an inordinate amount of brain-juice to produce this email, and probably a correlative amount to consume it. So I’m trying a streamlined process this time around: the process of no process. Enjoy. (Update before I hit send: It didn’t work.)

Conspiracies

It’s Chinatown

Turned to Good Account

The Context of No Context

Perception and apperception

Responsible independence of thought

Without burying the lede (as I so often do): I’m teaching a book club on The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon’s brilliant second novel (and his shortest—great place to start if you’ve never read Pynchon), over four Wednesdays starting July 13. It’s offered on a sliding scale from $75-$225, and it’s going to be a blast. My book club on Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse was so much fun that I’ve been trying to find a next book to teach (see below), and have finally settled on this. (And I’ll be teaching To the Lighthouse again in September, too.)

If you’re unfamiliar: The Crying of Lot 49, published in 1965, concerns itself with the adventures of one Oedipa Maas, who has just been appointed “executrix” of her former lover Pierce Inverarity’s estate. In the course of carrying out her duties, Oedipa finds herself on an odyssey involving a warped psychoanalyst, a hard-living lawyer who seems to pre-echo a Hunter S. Thompson character, a 60s pop band, an obscure Jacobean revenge play that comes in for some very post-modern textual deconstruction, and, most of all, a global conspiracy involving a shadowy mail-delivery service that is bent on world domination, world enlightenment, some combination of the two, or something else altogether. There’s also a healthy portion of actual history thrown in, including the real Thurn und Taxis postal system, which itself is fascinating to read about if you’ve never come across it before.

(Re that: Things seem to have worked out okay for the Thurn and Taxis family. They even spawned a socialite who is apparently known by the moniker TNT, and whose living room—or, one of them—is pictured above.)

A lot has been written about Lot 49; I’ve read almost none of it. The book is so dense and rewarding, it’s one of those texts that reveals more and more each time you read it. It’s a wild ride, but one that leaves you seeing the world in a different way once you step off—which is, by some measures, as much as any novelist can hope for from their work. I hope you’ll join us.

It’s Chinatown, Celeste

I mentioned last time that I’m editing a new column for Alta Journal: You Are Here is written by members of The Writers Grotto and will feature ideas of place and stories of places in the west. At the time, my introducer was the only piece that had been published, but I’m happy to say that the first entry in the series has now dropped. It’s a piece by Celeste Chan, about finding community on a volunteer safety patrol of San Francisco’s Chinatown, during a time of COVID anxiety and rising hate crimes against Asian Americans. I’m really happy with how we were able to mix themes of place with Celeste’s story of finding her own place within this community she didn’t initially feel a part of. Give it a read, and give it a boost in your social media, if you like:

Timethrift update

Wow, I’m really having a hard time not spending a lot of time organizing my thoughts here. What I’m trying to avoid is wasting my time and yours unnecessarily. So I’ll talk about a word I thought I’d coined: timethrift. Like spendthrift, it would mean someone who uses their time (as opposed to money) unwisely. Sample sentence: “I’ve been a real timethrift in composing this newsletter in the past.”

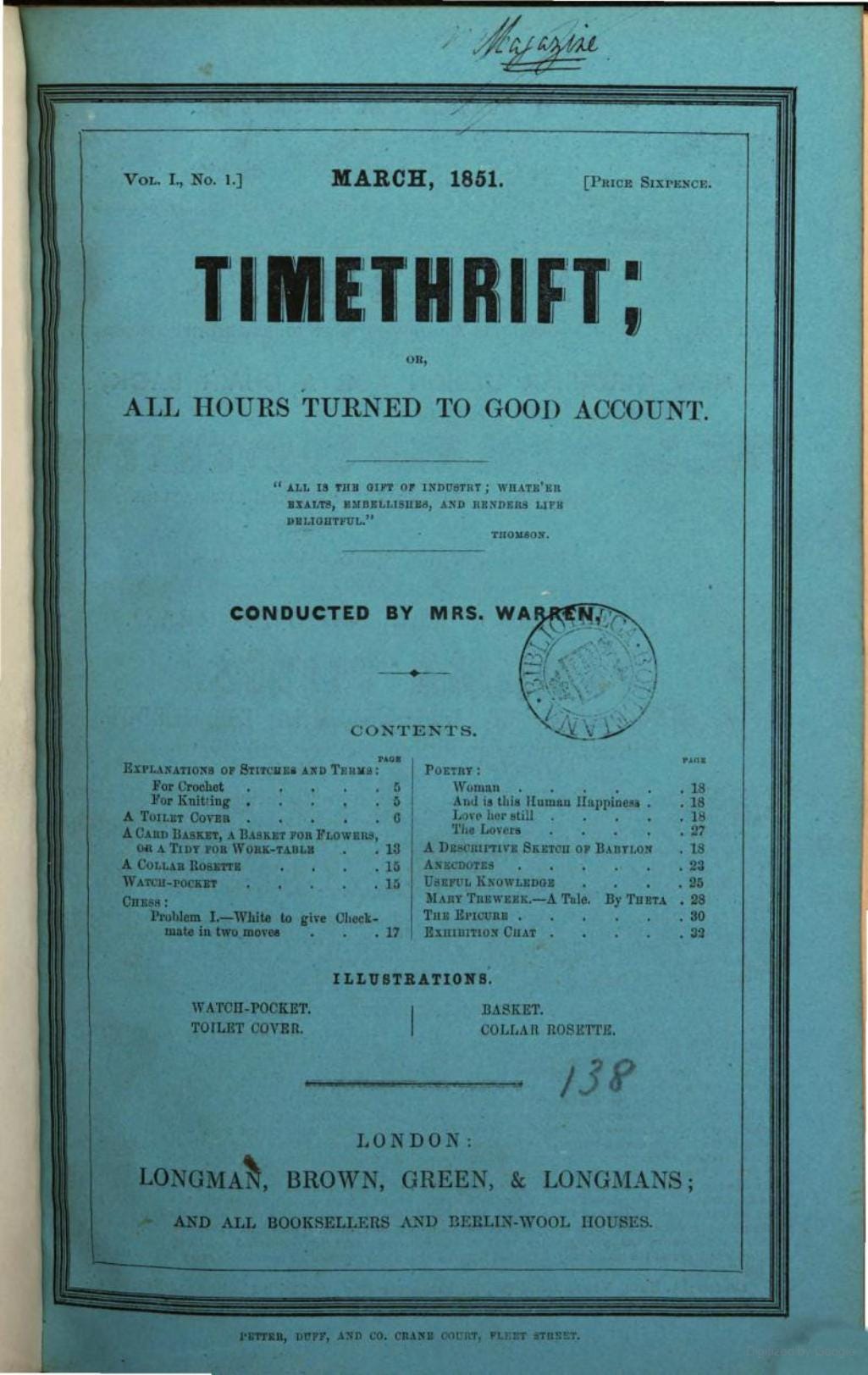

Happily, I find some prior art, including this fantastic 1851 magazine, Timethrift; All Hours Turned to Good Account.

(Note that it is “Conducted by Mrs. Warren,” which I love.)

It’s filled with crocheting patterns, a chess problem, poetry, brief instructive anecdotes, and more. There’s another magazine—from the following year, oddly—The Leisure Hour, which offers Hints About Timethrift. It seems like people had a lot of time on their hands in the middle of the nineteenth century.

I offer these merely as curios, in the spirit of the process of no process.

Readings in Context

Speaking of the process of no process: One of my favorite books is a slim, obscure volume (no surprise) called Within the Context of No Context, by someone with the unlikely name George W.S. Trow Jr. Trow was a New Yorker writer and son of a newspaperman, and the book combines an issue-filling essay he wrote for the magazine in 1980 with a follow-up piece (more autobiographical) he wrote nearly 20 years later. It’s an incredible take on media culture, on the damage that television was doing through its decontextualizing of daily life, and on the dire portents for the future should the situation continue—ominous bodings we seem to be living through today. I highly recommend this book, not just as cultural commentary, but because it’s also a really interesting model for how to put together a long piece of nonfiction, combining criticism with personal narrative in an incredibly insightful way. We might call this authotheory today. (Caveat: I last reread this book about five years ago, and though the details of this escape me now, I recall thinking that there was certainly a bit of unexamined straight white male privilege that weaves through the book, though not in a way that undercuts its arguments, imo.)

Perception and apperception

In a way, Trow’s book is about how the views of the world we’re presented with shape how we in turn view the world. This of course has proved to be extremely germane to our present moment—perhaps the thing most germane to it, in fact. And by extension: Do you perceive the world as zero sum (one person’s gain is another’s loss), or as abundant (there’s enough to go round for all)? This, to me, more than any other philosophical divergence, explains the divisions we’re seeing in society today.

But I’m no philosopher, I just love words—one corollary of that condition being that I too often try to put words and explanations to phenomena that might be better off just left observed. In any case, it’s that observation that interests me at the moment: the ways in which we perceive. And what I perceive is that all the books I’ve mentioned here, quite without intending it, are books of perception, in some way.

The Crying of Lot 49 is a book that’s very much about how we see the world. Is Oedipa Maas really caught up in a global conspiracy? Or does she just perceive one, whether or not it actually exists? What’s really interesting about her story is that her experience investigating this question changes how she perceives the world. (I once consulted on a really interesting project: An immersive gaming experience that cast its players as members of a fictional secret society. But riddle this: What’s the difference between a real secret society populated by adherents, and a fictional one populated by player-participant audience members?) In one reading (among many, many other possibilities), Lot 49 offers us the chance to awaken to a dazzlingly interconnected world, and to enjoy being surrounded by those connections, whether they be fictional or real.

To the Lighthouse asks related questions of perception, though perhaps on a more inter/personal level. What can we know by looking? How can this help us connect? What does it mean to realize one’s personal vision of the world? If Lot 49 examines these questions from the outside in—How does my perception of the workings of the world shape who I am?—TTL, more existentially, gazes out from within: Can I really know and connect to the things around me, or am I alone within myself? Here again: it’s one reading among many. YMMV, as the internet kids (used to) say.

Lastly

On a similar note: A colorful old friend of mine (RIP, Mr. Village) was fond of quoting heavyweight American philosopher John Dewey, to the effect that “perception is the apperception of the apperceptive faculties.” I can’t find that quote right now (and my friend may have made it up), but I did run across another Deweyism that’s applicable to this newsletter and this moment in the world: “A society with too few independent thinkers is vulnerable to control by disturbed and opportunistic leaders.”

The second half of that quote is instructive as well: “A society which wants to create and maintain a free and democratic social system must create responsible independence of thought among its young.”

If you know anyone young, please pass on to them the habits of “responsible independence of thought.” If you happen to be young (by which I mean: still breathing), please practice them yourself.

Til next time,

Wallace